What Will Happen When They Come After You?

- If you have a socially or environmentally conscious business…

- If you are an activist on any issue…

- If you work in any way to better the lives of disempowered people—whether the disempowerment is social, cultural, medical, geographical, or any other cause…

Please read this next paragraph VERY carefully. It’s from today’s Letters from an American by Heather Cox Richardson (emphasis added):

How religion and authoritarianism have come together in modern America was on display Thursday, when right-wing activist Jack Posobiec opened this weekend’s conference of the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) outside Washington, D.C., with the words: “Welcome to the end of democracy. We are here to overthrow it completely. We didn’t get all the way there on January 6, but we will endeavor to get rid of it and replace it with this right here.” He held up a cross necklace and continued: “After we burn that swamp to the ground, we will establish the new American republic on its ashes, and our first order of business will be righteous retribution for those who betrayed America.”

This is a major Washington conference of influencers. Take it seriously! That is one of many ways fascism rears its ugly and dangerous head. Trump actually quoting Hitler, repeatedly, without attributing him is another. A series of Supreme Court decisions and new repressive state laws add more heads to this horrible Hydra.

The good news is they can’t do this without our help. Staying home on Election Day helps the wannabe fascists. And since most parts of the US don’t have ranked-choice voting yet, so does voting for a third-party candidate in the general election. Oh, and showing up helps our cause and hurts theirs. Show up to lobby your Members of Congress and your state and local elected officials. Show up in the streets to participate in protests against harmful policies or support demonstrations for those you favor. And show up to vote!

If, as I do, you disagree enough with Biden’s policies that you have a hard time voting for him, show that in the primary. Show up to vote and don’t vote for him. Either leave the president line blank or vote for an alternate candidate. My Primary is March 4 and I will either vote for Dean Phillips, who is slightly left of Biden, or write in Green Party candidate Cornell West.

But I recognize that Biden, barring some major development like a major health crisis, will be the nominee. And even though I live in a reliably Blue state, I recognize that his likely opponent will contest the results if they are anything less than an overwhelming victory for Biden.

And let’s not forget that Trump has promised to be even worse on immigration—and on many issues—than he was during his time as President.

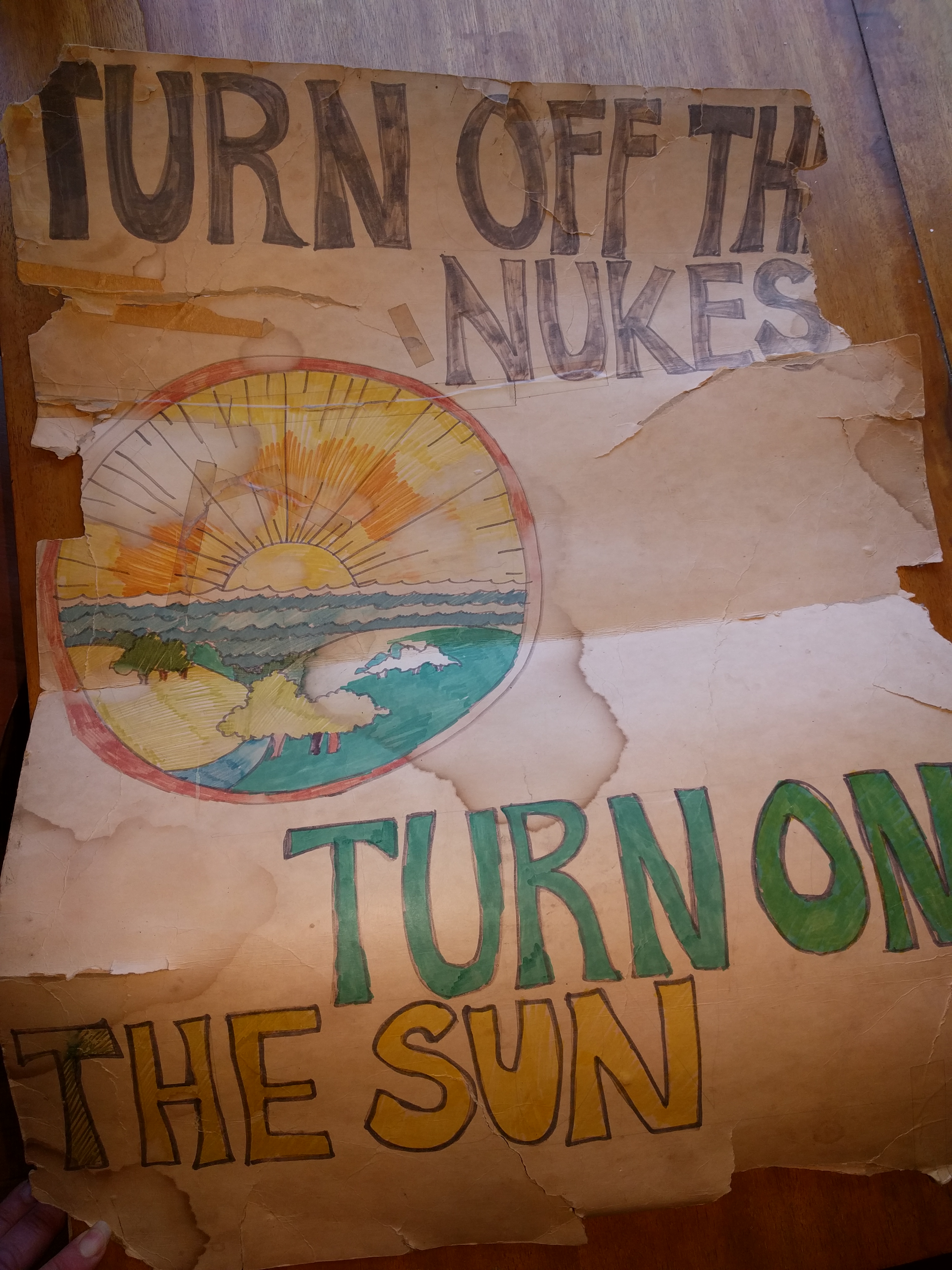

I want that margin to be as big as possible, so come November, I will cast my vote for democracy and against fascism, despite Biden’s betrayal of his campaign promises on issues that include unnecessarily harsh positions on immigration and his relentless support of the brutal regime in Israel and its devastation of Gaza, despite his energy policy that doesn’t do nearly enough to curb fossil fuel and embraces the false narrative that nuclear power is part of the climate solution (I’ve written a book on this; nuclear is a problem, not a solution), and despite many other reservations.

Remember the prophetic words of anti-Nazi Pastor Martin Niemöller

First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a socialist.

Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a trade unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.

And speak out! Speak out for the socialists, the trade unionists, and the Jews. Speak out for Arabs and Muslims, for immigrants from anywhere, for people in the LGBTQ community, for those with disabilities, for those who Trump has threatened with retribution that includes rounding up and detaining opponents.

Speak out. For democracy. For decency. Speak out, ultimately, for yourself.

Check out this

Check out this