This Power-Grabbing Bill Puts Us ALL In Danger–But We Can Stop It!

Of all the eamples of greenwashing I know, none is more insidious than the way the nuclear power industry pretends to be green. In reality, it’s super-dangerous, with at least a dozen serious issues that threaten our liberty,our property, and our very lives. Nuclear power is unsafe, uneconomical, and is not a solution to the climate crisis. My first book was about this, and when I updated it after Fukushima for a Japanese publlisher, I saw that it was still unviable, and still a threat.

If you live in the US, the Senate and House will be going to conference committee to workout their different versions. And this is our chance to stop this horrible bill from becoming law. Below is the letter I’m sending to my Senators, which contains a lot of information about the issue. If you are moved to take action, please copy or modify it and send it it to your own Senators and Representive. You can reach them easily by clicking the Senators button at http://senate.gov and then selecting your state. You also have my permission to share it widely, including with groups you’re involved with and with the media. Don’t forget to change the blankline to the recipient’s name. I usedthe subject line, “Please STOP the Price-Anderson Act renewal–our lives depend on it”

Here it is (note that I have removed the fronts of web addresses because at least some Senators block a submission that has many hyperlinks):

Dear Senator ________:

As your constituent, I urge you in the strongest possible terms to REMOVE the giveaways to the nuclear industry from the reconciliation package. If we examine the package closely, we discover that:

1. It RENEWS the grossly inadequate and highly taxpayer-subsidized insurance “protection” of the Price-Anderson Act for 40 (House version) or 20 (Senate version) years, leaving the public almost completely unprotected from financial loss in the event of an accident. This is one of the worst bills ever signed into law, capping insurance payouts for nuclear accidents at absurdly low levels. Price-Anderson originally capped the federal share at just $500 million per accident plus another $60 million from the utilities, according to the 1969 book Perils fo the Peaceful Atom by Richard Curtis and Elizabeth Hogan, pp. 194-195. The private utility coverage has since expanded through secondary coverage, with nuclear utilities retroactively assessed to cover up to $16.097 billion per accident, according to a January 2024 report to Congress by the Congressional Research Service, crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10821. By contrast, actual dollar losses from the single 2011 disaster at Fukushima are estimated at $20 trillion—more than 1000 times as much (see ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK253929/#:~:text=The%20total%20cost%20of%20the,Bottom%20nuclear%20plant%20in%20Pennsylvania ). Property owners and taxpayers are expected to make up the difference. And this doesn’t even count non-dollar or indirect costs such as injury and death, loss of land for generations, forced relocations, loss of agricultural revenue, and more. According to this Newsweek report, 14,000 people were forced to relocate after the Chernobyl accident closed a 1040 square-mile area back in 1986 (38 years ago)—and scientists don’t expect that area to be safe again for at least 3000 years. See newsweek.com/chernobyl-aftermath-how-long-will-exclusion-zone-uninhabitable-1751834

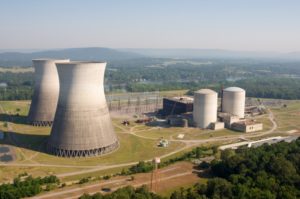

2. It REMOVES much of the licensing oversight from new nuclear power plants. These are crucial protections for civilians. The nuclear power industry has had a long history of not factoring in things like earthquake faults when siting n-plants.

It is also important to note that well beyond the three catastrophic accidents (Fukushima, Chernobyl, and Three Mile Island) we all know about, there have been at least 133 potentially serious accidents just in the brief span since the birth of the industry in the 1950s. See en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_nuclear_power_accidents_by_country. We have been extremely lucky that only three wreaked significant damage.

Finally, the claim that nuclear is necessary as a tool to fight climate change is false on three counts:

• Clean, renewable energy can do the job better, more reliably, and MUCH faster (see sciencealert.com/here-s-why-nuclear-won-t-cut-it-if-we-want-to-drop-carbon-as-quickly-as-possible , sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2214629618300598 , and https://clamshellalliance.com/statements/statement/ )

• Many parts of the nuclear power cycle other than feeding radioactive materials through a reactor have a big carbon cost (see nrc.gov/docs/ML1014/ML101400441.pdf , especially Page 2)

• When something goes wrong, as noted above, the detriments far outweigh any potential benefit.

It is long past time to end the subsidies for this dangerous, economically unworkable, and poorly performing technology and turn our attention to the real solutions such as solar, wind, and geothermal—and energy conservation/efficiency, which are the low-hanging fruit (see eia.gov/energyexplained/use-of-energy/efficiency-and-conservation.php ). I urge you to not only support true green energy but to convince your colleagues to block this terrible initiative.