The Window to Save Our World Is Narrowing—But Not Closed

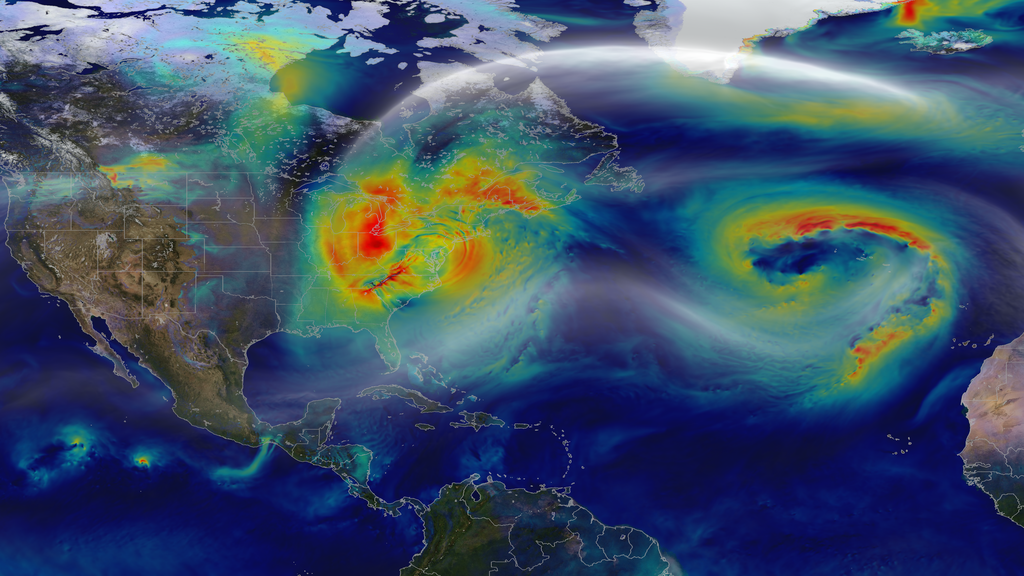

A friend posted her fears that the extreme weather we’ve pretty much all been experiencing is only going to get worse…that coastal cities (which includes most of the world’s great centers) are going to be hammered by storms that will make Hurricane Sandy—which wreaked havoc in NYC and elsewhere—feel like a gentle rain…wildfires that consume vast acreage, depleted aquifers that cannot regenerate and can no longer supply our farming needs…

I agree with her that the current path will lead to multiple calamities. But I remain optimistic that the rapidly closing window to fix it is still open for now; we can still reverse the destruction. We know how: innovation has reached astounding levels in the last 20 or 30 years, and we humans have developed and piloted hundreds of cool technologies and processes that accomplish multiple good outcomes with zero-to-minimal harm.

But we are 50 years late in making meaningful progress and we can’t be wasting time debating whether human-caused climate change is real. Nearly unanimously, scientists who are not funded by polluters agree that humans have accelerated climate change significantly. And even if the climate change is nothing more than the earth making course corrections, we still need to address/reverse/prevent the effects if human civilization is going to continue in anything like the way we know it.

With light editing for context and to mask the identities of others who posted in the thread, this is my response:

My Response to the Gloom-and-Doom Post

One thing we can all do—homeowners, tenants, farmers, business owners—is STOP SQUANDERING CLEAN WATER! We waste far more than we actually consume, and this has serious consequences as aquifers dry up. I just read this morning in a book called The Sustainabiity Scorecard that certain prescription drug manufacturing processes generate up to 7700x the product weight in waste, most of it water. I’ve said for more than 20 years that while our descendants might forgive us for squandering oil (which has substitutes), they will NOT forgive us for squandering water, which is essential to life.

Like most pieces of climate change, we’ve known how to fix the problems for decades—but we can’t find the political will. We should be living in a circular economy by now, where waste is transformed into input. We should be powering that economy with clean and renewable power sources including not only the common ones like solar and wind but more advanced, less well-known technologies like harnessing light and natural electrochemical reactions (see Gunter Pauli, The Blue Economy 3.0). We have known how to do this since at least 2001, and we’ve known we need to do it since at least 1970. This is our last chance to get it done before the scenarios [the original poster] is worried about become everyday reality—and lead to constant civil unrest, widespread famine, and various other calamities that dwarf anything we’ve experienced. Science fiction writers like John Brunner have been describing that awful world for generations, because they could see the logical consequences of hiding our heads in the sand and pretending everything can go on as it has.

BTW *I* am actually an optimist on this. I believe we can still fix it, but we damn well better hurry up and commit society to solving these interrelated problems just as we committed ourselves globally to de-fanging COVID (with amazing success in a very short time)—but the longer we wait, the harder the task. The window is closing while we squander the 50-60 years we’ve had to get it done.

And thus I AGREE with [another commenter]’s paragraph about mitigation. Yes, engineers and designers can fix a lot of stuff—especially if they come in not attached to particular solutions but look holistically at how integrated solutions can not only address multiple problems at once (e.g., climate, waste disposal, water and food insufficiency, human comfort) but provide lots of jobs and community revitalization at the same time. But too many engineers have been trained in the existing, failing ways of thinking. We need to think circular and lifecycle impacts (including end-of-product-life disposal or repurposing), with closed loops, zero waste, net energy consumption, or pollution, etc.—and not linear thinking that only acknowledges processes production cost. Engineering as usually practiced has a tendency to externalize things like disposal costs onto the backs of us taxpayers and our progeny.

I also agree that we need to look at pollution, waste disposal, etc. in other industries including chemicals and battery manufacturing, and I don’t see electric cars or solar panels as panaceas.

But I totally disagree with most of his other points. The overwhelming scientific consensus, at least of scientists not funded by fossil companies or others who would have to drastically alter their processes (and temporarily lower their profitability) to fix the mess they helped create, is that human-caused climate change is real, and extremely dangerous.

[Original poster] brings up fusion, as she often does. Fusion sounds great in theory, but I’ve been hearing for my whole life that it’s just around the corner, and yet we never turn that corner. We can’t sit around waiting for fusion. The most optimistic predictions still put it pretty far down the pipe as a mainstream energy source. Yes, let’s keep the research going, but meanwhile, dig ourselves out of this deep hole of our own making.

I know [the original poster] is also a fan of small-scale nuclear fission, but I am not. [In her response to my comment, she corrected me and said she is not either.] If you want to know why, visit https://clamshellalliance.com/statements/statement/ (disclosure: I provided some minor help in writing this, particularly the section on accidents). I have some expertise here: my first of ten books was on why nuclear fission is a big mistake. It was written in the aftermath of Three Mile Island (as a revision/update of a much older book by my co-authors) and I updated it again—for a Japanese publisher—after Fukushima.

Several years ago, I brainstormed a list of 111 things the average person can do to reduce carbon and water footprints. It’s not comprehensive, it’s not necessarily the most important—it’s just one person’s brainstorm from around 2009. It retails for $9.95 but I’m giving it away. Just visit https://goingbeyondsustainability.com/#Freebies and click “Painless Green” (yes, you will need to provide your email and subscribe to my monthly newsletter—but you can unsub if you don’t like it).