George Lakey on How We Win

I listened to a great 2018 talk, “How We Win,” by one of my many mentors, nonviolence theorist George Lakey (that’s the first chunk. You’ll see a link on that page to Part 2.). How We Win is also the name of his latest book at the time.

Lakey sees the increasing polarization of modern US society as a forge: a way of generating the heat necessary to create lasting social change (toward freedom and equality or toward authoritarianism—“the forge doesn’t care”).

This is not a new trend. The Scandinavian countries had their huge social revolution of the 1930s in times of great polarization (something he chronicled in his earlier book, Viking Economics). The trick is to harness that energy and channel it toward gaining mass support. He walks his talk, too; in the summer and fall of 2020, he led or co-led numerous workshops on what to do if the Trumpists tried to seize power after losing the election, training thousands of people.

He charges us to express our best concepts—not just what’s wrong with the system but the vision to make it better—in ways that feel like common sense to working-class people who want the system to work for them, too. After all, most of us actually do want a system that promotes equal access, a fair economy, and real democracy. We have to show them that our vision “has a spot for you,” even if that “you” finds the movement’s tactics disruptive and uncomfortable.

But he says progressives have largely lost that vision since the 1970s; we need to get it back. If we can get the diverse movements working together to confront their common opponents, we foster an intersectional “movement of movements” capable of creating real change—as the Scandinavians did then, with farmers, unionists, and students joining together to drive the moneyed elite from power. He warns us that polarization will get worse, because economic inequality is built so strongly into the culture. He says that we should consider organizing campaigns as “training for [nonviolent] combat.”

And we should expect those campaigns to take a while. Campaigns are well-planned (but adaptable) and sustained over time. It might take years, but you can win. One-offs (like the Women’s March at Trump’s inauguration) don’t typically accomplish change on their own. Traffic disruptions don’t make change; they just piss potential allies off. Disrupting banking operations is much more strategic because the bank is the perpetrator of the evil. How is the specific goal of the campaign advanced by this action? If it doesn’t advance the cause, don’t do it. A campaign he was involved with moved $5 million into credit unions and cooperative enterprises in one campaign that started in a living room and grew to encompass 13 states.

Oppression is only one lens we can look at things through—there are many others (he didn’t elaborate). The elite seeks to divide us (by color, gender, values, etc.)—but canny organizers look for the cracks in those divisions, and expand them. And stays optimistic, not getting stuck in “can’t be done” but figuring out how to do it.

Campaigns often start small. We can build our skills when the stakes are lower and make our mistakes then. Later, as the big challenges arise, we know how to handle them. You can lose a lot of battles and still win the campaign (eventually). And any tactic will be greeted with “this will never work” skepticism. But “Anyone who is arguing for impossibility” should remember the Mississippi Summer volunteers. When news got out of the abduction of Goodman, Schwerner, and Cheney, Lakey (a trainer of volunteers for trhat movement) expected most of the next volunteer wave to abandon their commitments—but nearly all of them stayed, mentored by Black SNCC activists who had been living with the overt racism for decades.

The best-known antidote to terror is social solidarity. Get close to people. Organize campaigns not just with those who share your goals but those who are “willing to be human with you.” Make your peace with the personal risk, face it head-on. We risk by driving on the highway, we risk by NOT meaningfully addressing climate change. Accepting the possibility that you might die in service of the common good is liberating (and it’s not the worst way to die).

SNCC survived in the Deep South without guns; they would not have survived with them. Erica Chenoweth shows us that nonviolent movements have twice the success rate of violent ones.

Framing is crucial. The Movement for Black Lives put out a mission statement that was so well framed, even American Friends Service Committee signed on [I think it might be this one].

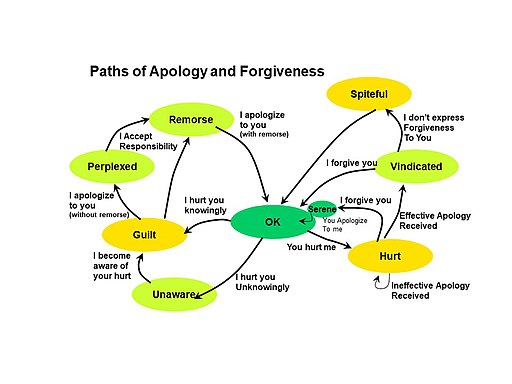

If you want innovation, conflict helps to get you there. Yet, conflict resolution is a crucial skill, and it’s expanded enormously in recent decadesWe need those tools and people who will jump into the fray (to use them). But if our tools are too highly structured, you need to add interventions in informal settings.

Lakey expects surveillance and isn’t worried about it: “I think it’s a wonderful thing. We take that as pride: we are so important that they put staff time and energy into knowing what we’re up to—so we’re making a difference. Gandhi told India, if you gave up fear of them, the British would be gone. If people spread fears about Trump, invoice him for the hours because you’re doing his work.”