A Religious Imperative to Heal the Earth: Climate Arguments to Influence People of Faith

You won’t normally see me starting a blog post with a bible quote, but…I’m quoting an article that quotes the Bible:

In Genesis 1 God commands humanity: “Fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground” (1:28). “Subdue” and “rule” are verbs of dominance. In Genesis 2, however, the text uses two quite different verbs. God placed the first man in the Garden “to serve it [le’ovdah] and guard it [leshomrah]” (2:15). These belong to the language of responsibility. The first term, le’ovdah, tells us that humanity is not just the master but also the servant of nature. The second, leshomrah, is the term used in later biblical legislation to specify the responsibilities of one who undertakes to guard something that is not their own.

–Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks

The Jewish year divides the Old Testament into weekly portions that stay the same year after year.

My politically conservative, religiously Orthodox brother-in-law sent me the article I quoted, “The Ecological Imperative.” It turns out to be last week’s installment in a weekly series by a British rabbi on each week’s parshah, the Torah reading for the week. The readings assigned to each Hebrew-calendar week have stayed the same year after year, for centuries.

Joe knew I would like it. He didn’t know I’d be fascinated enough to write a whole blog post about it. I will share my takeaways from this article–but let me provide some personal background first.

My Back Story

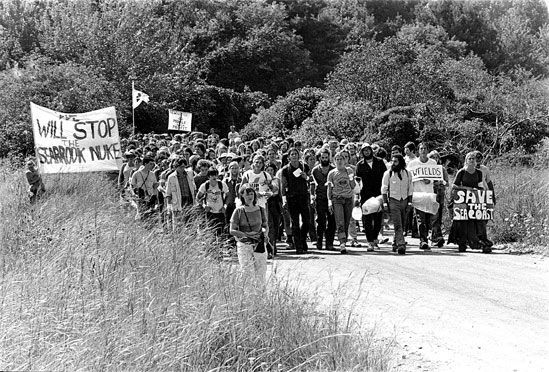

I was a convert of the very first Earth Day, back in 1970, when I was 13. By 1971, I had joined my first two environmental advocacy organizations (one in my neighborhood, the other at my high school). That activism (and the lifestyle choices that support it) have been a strong part of my life ever since.

But my motivations back then were entirely secular. Three years earlier, my mom and dad had split up, and both parents had stopped being religious. I had moved from a yeshiva (religious school) with half the day in Hebrew to the regular public school. And as someone who’d not only been very frustrated with the many social and activity limits of Orthodox Judaism but who independently had questioned the existence of God by age 9, I welcomed those confusing changes in my life.

It was only many years later that I began to make space for a sense of faith. My image of God is very different from the classic image of the old man with a beard, throwing lightning. I don’t consider myself religious–but I can’t truthfully call myself an atheist.

In 2017, I began a process of reading major religious texts, starting with the Five Books of Moses, then continuing through the Four Gospels of the New Testament and now the Qur’an (Koran). So I’ve read Deuteronomy fairly recently. Of those nine books of the Old and New Testaments, I found Deuteronomy the most tiresome and challenging by far. It is largely a regurgitation in Moses’s voice of Leviticus and Numbers. As my secular side perceived it, it was a collection of random rules that made no sense in the modern world and maybe not much sense in the ancient world either.

Putting the Parsha in Context

But Rabbi Sacks reaches back from the week’s Deuteronomy 16:18-21:9 parsha (“Shoftim”) to the second chapter of Genesis, to show how the sages over these centuries have placed the commandment not to destroy your enemy‘s natural resources during a siege into a broader context of planetary stewardship, and even planetary healing.

The Sages, though, saw in this command something more than a detail in the laws of war. They saw it as a binyan av, a specific example of a more general principle. They called this the rule of bal tashchit, the prohibition against needless destruction of any kind. This is how Maimonides summarises it: “Not only does this apply to trees, but also whoever breaks vessels or tears garments, destroys a building, blocks a wellspring of water, or destructively wastes food, transgresses the command of bal tashchit.”[1] This is the halachic basis of an ethic of ecological responsibility.

Lessons and Takeaways

- Specifics in the Torah (and by extrapolation, other holy texts from other traditions) can be extrapolated to determine sweeping codes of social behavior/social responsibility.

- The texts support an earth-friendly interpretation that provides defense against the argument that the Bible commands us to subdue the earth and its other inhabitants.

- More than that, if we take these texts as the word of God, we are commanded to treat the earth as God’s creation, to treat it with great respect, and to maintain its abundance and its health for future generations.

- Given this imperative and the rapidly-closing window to solve the climate crisis, if we agree with #3, we have to support a political and business structure that encourages action. Presently, we face not only a global climate crisis (which I believe is still solvable through a combination of innovation and regulation), but a bunch of governments around the world, from the US to Brazil to the Philippines, that are actively attacking measures to preserve the environment (and, not coincidentally, attacking human rights at the same time). Just as Pope Francis’s climate encyclical provided impetus within the Catholic community, Rabbi Sachs’s interpretation can perhaps light a nonpolluting, non-carbon fire among religious Jews and even among Evangelicals (who of course see the Old Testament as part of the Word of God).

- The planet can’t speak up in front of a legislature or at the UN. So let’s get some movement going to get leaders who will speak on its behalf!

.