40 Years Ago Today, We Changed the World (Part 5, Fighting the Battle Again)

If you missed Part 1, read it here, and then follow the links to Parts 2, 3, and 4.

Chernobyl and Fukushima

Chernobyl rendered a big swath of Ukraine uninhabitable. While a few more travelers are gaining permission to enter the dead zone, nobody lives there, and nothing you’d want to eat grows there.

After that disaster, the nuclear industry experienced a long series of accidents that could have been very serious, but were contained.

Then came Fukushima.

While it wasn’t nearly as destructive as Chernobyl, it still contaminated a 11,500-square-mile area and required the permanent evacuation of 230 square miles (evicting—and causing massive economic loss to—159,128 people). Much agricultural land had to be abandoned. Japan shut of most of its nukes for several years, causing great economic stress and forcing more intensive use of carbon fuels to replace the lost energy in a hurry.

And the world discovered that nuclear power plants, which are usually located next to water for cooling purposes, are not designed to withstand a significant flood.

I had written my first book about why nuclear power makes no sense, published all the way back in 1980. Following Fukushima, a Japanese publisher tracked me down and asked about bringing it back into print. I researched and wrote ten-page update that convinced me that nuclear power is still an absolutely terrible technology. If you’d like a copy, please download at https://greenandprofitable.com/why-nuclear-still-makes-no-sense/

Zombie Nukes are Back from the Dead

The safe energy movement made nuclear energy too expensive economically and politically for many years. But all of a sudden, the zombie power plants are back from the dead.

The two-reactor Watts-Bar plant in Tennessee was permitted back in 1973, but even more than most nukes, it was plagued by delays. Unit 1 took 23 years, going on-grid in 1996. Unit 2 took another 20 years, going online in late 2016. No US nuclear plants went online between those two dates. And meanwhile, these plants use obsolete, unsafe, 1970s design—a frightening specter.

A newer design, the Westinghouse AP1000, was selected for the two double reactors permitted during the George W. Bush years in Georgia and South Carolina. The idea was to prefabricate much of the reactor and thus shave time and costs. Instead, however, the plants have faced delays of many years, massive cost overruns, safety crises, and the resulting bankruptcy of Westinghouse (and near-collapse of parent company Toshiba).

The crazy thing is this: never mind the safety issues, the citizen opposition, or all the other stuff—why would anyone want to tie up billions of dollars for a decade or more constructing an n-plant that will never be economically competitive, uses unproven technology, and generates enormous opposition? There are very good market-based reasons why the US nuclear industry shriveled up after Three Mile Island. It’s hard to imagine any sane company or investors going there.

The Carbon-Friendly Magic Bullet Myth

The last several years, some environmentalists have embraced nuclear because they think it’s a big step forward on the path to a low-carbon planetary diet.

But they’re wearing blinders:

- Why do we want to reduce our carbon footprint? To protect the earth! Ask people who used to live near Chernobyl or Fukushima and were forced to evacuate if they think nuclear protects the earth.

- It takes over a decade to get a nuclear plant built and generating power—and that’s when everything goes smoothly (which is almost never, as we’ve seen). Climate change is an emergency and we can’t wait decades to solve it.

- We can lower that carbon a lot faster by investing in true green solutions. Rocky Mountain Institute’s Amory Lovins notes that dollars invested in conservation and renewables will reduce carbon up to 10 times as effectively and 40 times faster than dollars invested in nuclear. I quote his figures in some depth on Page 10 of the Fukushima update.

- Nuclear has quite a bit more carbon impact than most people realize. Every step in the process other than actually running the fuel through the reactor—and there at least eight other steps—adds to the carbon footprint (and consumes fuel, too): mining, milling, transportation, processing, building the reactor and the massive concrete containment vessel, removing the spent fuel, storing it for 250,000 years, etc. (It’s still less than fossil fuel, but it’s far from zero.)

The “Gen 4 Will Be Safe” Myth

The thorium and pebble-bed technologies do look better than the old boiling-water or pressurized-water designs, from my non-scientist/informed layperson’s perspective. BUT they are untested. And they will also take at best more than 20 years to come online, if all goes well (and history indicates that I probably won’t).

We know this: the Generation II nukes were supposed to be much safer than the Generation I plants, even though they were rated to generate up to 10 times as much electricity, and thus were built much more massively, with more things to go wrong. Gen II plants failed at Fukushima. A Gen II plant came close to failing several times at Vermont Yankee. Even when that plant was new, its safety report to the federal government was extremely disturbing, going on to document incidents for many pages within the first year.

The European Commission claimed at the time I wrote the update that Generation IV are the first nukes to be built with public safety integrated from the beginning. That creates yet another reason to shut down all the Gen I, II, and III plants (which are aging, going brittle, and increasing the danger to us)—and second, makes me wonder if in 20 years, after some of these plants have gone online and experienced catastrophic failures, if some scientists won’t be spouting similar rhetoric about Generation VI or VIII plants being the first to really be safe. The needle keeps moving on nuclear safety, as each previous reactor technology starts to fail.

Interestingly, the link I used in my post-Fukushima update now redirects to a page that does not make this claim, and in May, 2017, I couldn’t find anything about safety being built in to the new reactor designs anywhere on the organization’s website.

Lessons for Today’s Movements

We’d need a whole book to cover all the lessons today’s activists can bring back from the Clamshell experience. Here are a few of my favorites:

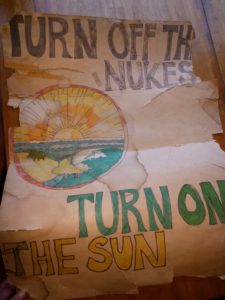

- Don’t just be against things; propose and organize for positive alternatives—and incorporate this in the framing you offer the media, the public, and to your opponents

- Remember not just your short-term goals but also the ultimate goals. Clam had a short-term goal of stopping the plant and a medium-term goal of stopping nuclear power nationally and globally. But Clamshell also had positive long-term goals. On energy, the goal was not simply to build a non-nuclear power plant but to power society through a variety of clean and renewable technologies—and on process, to move the whole society in a more democratic inclusive direction

- Organizing works best when you find ways of bringing the issues to the unconvinced—while not neglecting the deeply committed

- You can find allies where you weren’t expecting to

- When organizing people through active nonviolence, it will be much easier to win people over to your side; if you switch to violence, you’ll lose much of your natural constituency and your work will be harder

- Enforcing a rule that participants must be trained for actions with personal risk (such as arrests or physical harm) is a very good idea

- Agree on a governance structure, and stick to it (unless you get the whole group’s agreement to change it)

- Perhaps most important of all—understand that whether most of your movement believe you can win or believe you will fail, you’re probably right. Come in with the attitude that you WILL succeed, and the chances of succeeding become much higher. Stress this in all your outreach. Phrase things positively but realistically; don’t promise overnight results you can’t achieve. Emphasize that your fight is a long-term struggle, and publicly celebrate every small victory along the way.