8 Ways This Direct-Mail Copywriter Needs to Get a Clue!

Many years ago, I signed up for a Discover card for some very specific reason (it may have been in connection with buying an appliance from Sears, which owns Discover). I use this card so rarely that at least twice, when I’ve received replacement cards, I noticed that I had never bothered to activate the one that was about to expire.

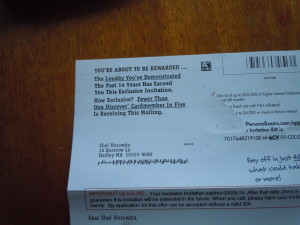

So I was extremely amused to get a very hypey 4-page mailer—it looks like the copywriter studied all the greats and completely misunderstood the lessons—that begins (bolding and underline in original—see picture),

YOU’RE ABOUT TO BE REWARDED …

The Loyalty You’ve Demonstrated

The Past 14 Years Has Earned

You This Exclusive Invitation.How Exclusive? Fewer Than

One Discover® Cardmember In Five

Is Receiving This Mailing.

And then it goes on to tell me I qualify for fast-track balance repayment that could shave a year and several thousand dollars off my repayments.

What’s wrong with this picture? Let me count the ways:

- As I mentioned, I’m not a loyal customer. I don’t even keep this card in my wallet. So I don’t believe the copywriter’s attempt to make this offer sound exclusive.

- Even if this were my primary card, I’m not exactly bowled over to learn that 20 percent of a user base in the millions is getting the offer. Exclusive? Ha ha ha.

- One more way to assure me this is nothing resembling the exclusive offer it pretends to be: the invitation code (required to participate in the program)—is 23 characters long, not counting hyphens.

- The lack of segmentation—OK, so this is the mailing manager’s fault, rather than the copywriter’s—is appalling. I never carry a balance. On ANY of my credit cards. I use them as 20- to 50-day access to funds without accruing interest, an easy way to track my purchases and save on postage (by paying one bill on line rather than a bunch of bills with mailed checks), and oh yes, a way to get air travel by accumulating frequent-flyer points for stuff I was going to buy anyway. So under any circumstances, I’m not even in the target market for this “exclusive” offer.

- The text of the letter is actually a strong argument against running up credit-card balances. It shows just how much this costs—something many consumers barely think about. The takeaway I get from this letter is don’t buy what you can’t afford, and pay your bills on time and in full, as I do, so you never pay these exorbitant charges.

- The meme of “make 2015 the year you took control” is ludicrous. You want to take control of your credit card debt? Pay off your balance and stop running it higher. Switching from five to four years of repayment servitude doesn’t cut it.

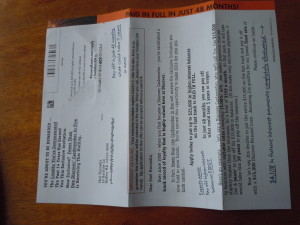

- Finally, the visual layout is a real turn-off. The thing is just drowning in too much bold, too much underlining (and the underlining is inconsistent—either underline the individual words or the phrases including the spaces, but don’t mix them), too many call-outs in a fake-handwriting font (does the designer really think we’re going to be fooled by the slight bowing in the underline?).

-

Page 1 of the lying letter from Discover Oh, yeah, on page two, which is even more cluttered with bold, underlining, and “handwritten” pull-outs, a footnote mentions that not everybody gets the spiffy 6.99% APR that “Jim” gets. Some people are going to pay usurious rates of up to 18.99%—YIKES!

It’s letters like this that give marketers a bad name.

This letter actually did inspire me to take action. First, I’m writing this blog. I get to use them as an example of how not to do direct mail. And second, I’m finally going to cancel my Discover card. I don’t choose to do business with companies that lie to me.

By the way, if you’d like marketing that doesn’t scream, doesn’t lie, addresses its exact target audience and effectively differentiates your products and services, give me a call at 413-586-2388 (8 a.m. to 10 p.m., US Eastern Time) or drop me a note. I make my living as a marketing and profitability consultant, with particular emphasis on green/socially conscious, businesses, independent small business, and authors/publishers.