When Does Activism Actually Make a Difference?

I posted a petition on Facebook, and someone commented, “Like this would make a difference?”

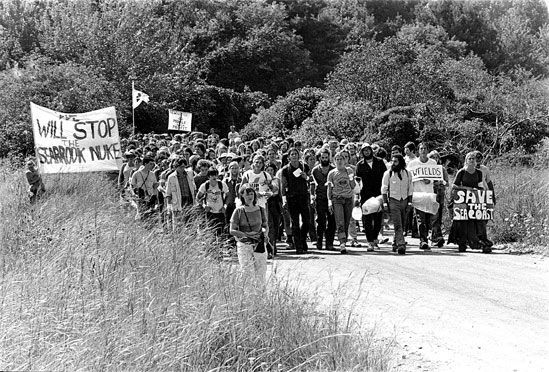

But here’s the thing: You never know what makes a difference. It was a pleasant shock to discover years later that Nixon was actually paying attention to the peace protests. I think the protests after the first Muslim ban and over the tearing of children from parents seeking asylum certainly made a difference. Amnesty International has made a demonstrable difference in the lives of thousands of political prisoners around the world. And I know that my participation in certain other actions, especially the Seabrook occupation of 1977, made a difference.

So we keep working and maybe sometimes we have far, far more impact than we thought we would. Who would have predicted how much traction the Arab Spring, or Tiannanmen Square, or Occupy would have gained, how much impact they had?

Who could have imagined in 1948 that all the Jim Crow segregation laws would come tumbling down, not only in the US but even in South Africa and Zimbabwe (then called Rhodesia)? Who could have predicted as recently as 2000 that same-sex marriage would be a legal right in all 50 US states and many other countries around the world? All of these victories are anchored in activism, sometimes decades of activism.

Who would have guessed that the incredible kids who survived the Parkland shooting on Valentine’s Day 2018 (toddlers when Massachusetts became the first state with marriage equality) would channel their angst into a movement that brought millions into the streets, tens of thousands to their voter registrars to register for the first time? Who knows which ones will grow up to be world leaders, and which long-time elected officials will be displaced by a wave of change?

In recent months, we’ve seen the cycle of impact quicken. Movements and memes that had been kicking around for years suddenly reach critical mass. Who would have expected the flowering of older and dormant movements such as #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter?

As an activist for more than 48 years, I remain optimistic, even in the face of so many defeats—because I also see these and many other victories. I see hope in so many people’s movements in the US, and in the complete change within two generations from a Europe ruled by power-mad fear-mongering dictators to one whose purpose actually seems to create a better world for the planet and its residents.

So yes, it makes a difference. Ordinary people can make a difference. Ordinary people make a difference constantly in fact: when I give my “Impossible is a Dare” talk, I cite examples like a seamstress (Rosa Parks) and a shipyard electrician (Lech Walesa) who changed their entire society.

What are you doing currently to make a difference? Please share in the comments.